Share this article

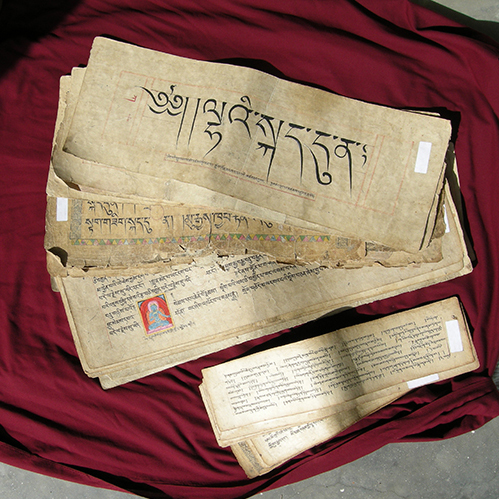

For centuries, Daphne paper has been traditionally handcrafted in Nepal and used to make Tibetan prayer books. But this was no simple feat. Acquiring the paper from the lower hills of Nepal and then printing prayers for students of ancient Tibet was in and of itself a journey.

Sitting in his cozy room on the 2nd floor of Triten Norbutse monastery in Kathmandu, Yongdzin Rinpoche, a 92-year old Tibetan Lama and most senior teacher of the Tibetan Bön tradition, recounts his memories on the importance that paper had in Tibet back then: “When I was a teenager, I began studying at the monastery. At that time it was not possible to buy any books. We needed to get paper ourselves and then get the book block printed. I went several times to Shigatse to purchase paper; a long way to walk, hard journeys.”

In Tibet, Daphne paper was known as Loshu, literally meaning “paper of Lo”, as in those days, the city of Lo Manthang, perched in the northern Mustang region of Nepal, was a traditional trading center between Tibet and Nepal. Although Tibetans purchased the paper in this high Himalayan region, the paper was in fact made further south in lower altitudes, where it was known as Lokta.

According to Yongdzin Rinpoche, at that time paper quality could vary a lot. While some sheets were very good, others displayed many impurities, going as far as sometimes having small twigs incorporated within the paper. The printing process required the paper to be slightly humid, so sheets were patiently laid out on the grass before printing.

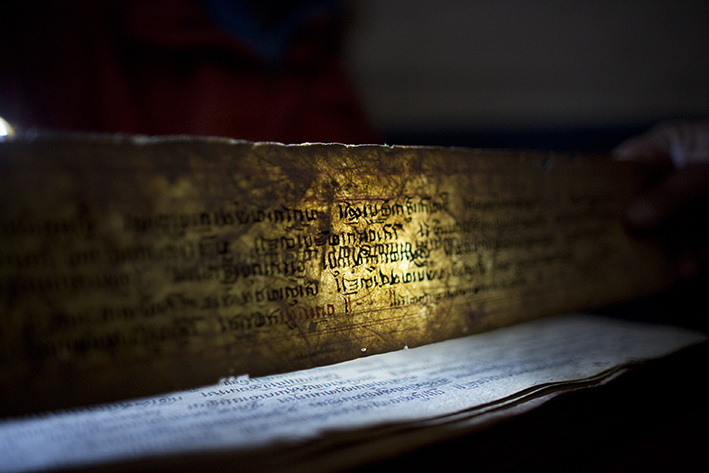

“Best quality paper was made with 3 or 4 layers of thin Daphne paper glued together with wheat flour. That was the paper mainly used for calligraphy. Not all prayer books were printed with carved woodblock, many were written by hand”, he adds. “The sheets are left to dry and made wet again by laying on the grass. Then they are smoothened with stones. The stones are beaten on the paper several times in all directions. This is really hard work. Then it becomes really smooth and even starts looking like leather, like parchment.”

Sometimes when paper was not available, it was also possible to make it in Tibet, but only in small quantities due to limited raw materials. This paper was made with the root of a flower called Reja. The roots were well cooked and beaten into pulp. In order to soften the fibers, a natural kind of soda was added. It was found in the form of white powder on the surface of some frozen lakes, brought by the Nomads. (This same powder was also used as soap in Tibet.) The treated pulp was then spread out on a wooden framed cotton sieve and left to dry in the sun, very much like the techniques used in Nepal.

“This paper was very white and very shiny, but the smell was very bad and could give headaches.” Yongdzin Rinpoche explains why Tibetans always preferred to use Nepal’s Daphne paper whenever possible.

In northern Tibet, far from cities, it was very difficult to find paper. In fact there was a time in Rinpoche’s life when he lived in Namtso, he remembers he could not find any paper there. Nomads came through only once a year, so his only choices were to either wait for their arrival or make a very long journey through the mountains on foot.

Hearing such incredible stories of ancient times – where the rarity of paper and its printing caprices made it a precious item, for which monks would literally embark on long journeys just to be able to record their prayers – reminds me of the important role this material has played in all of our lives. It is after all the sine qua non for all our stories, our knowledge and our artistic expression to exist and be shared through time! And yet we so very often forget it…

Share this article